Design Leadership: Crisis Edition

This is the transcript from my talk at this years Leading Design, it is at best a disjointed and rambling stream of consciousness, but possibly useful as historical context for the period we’re living and working through. I will update this post with the video once the conference organisers have posted them online.

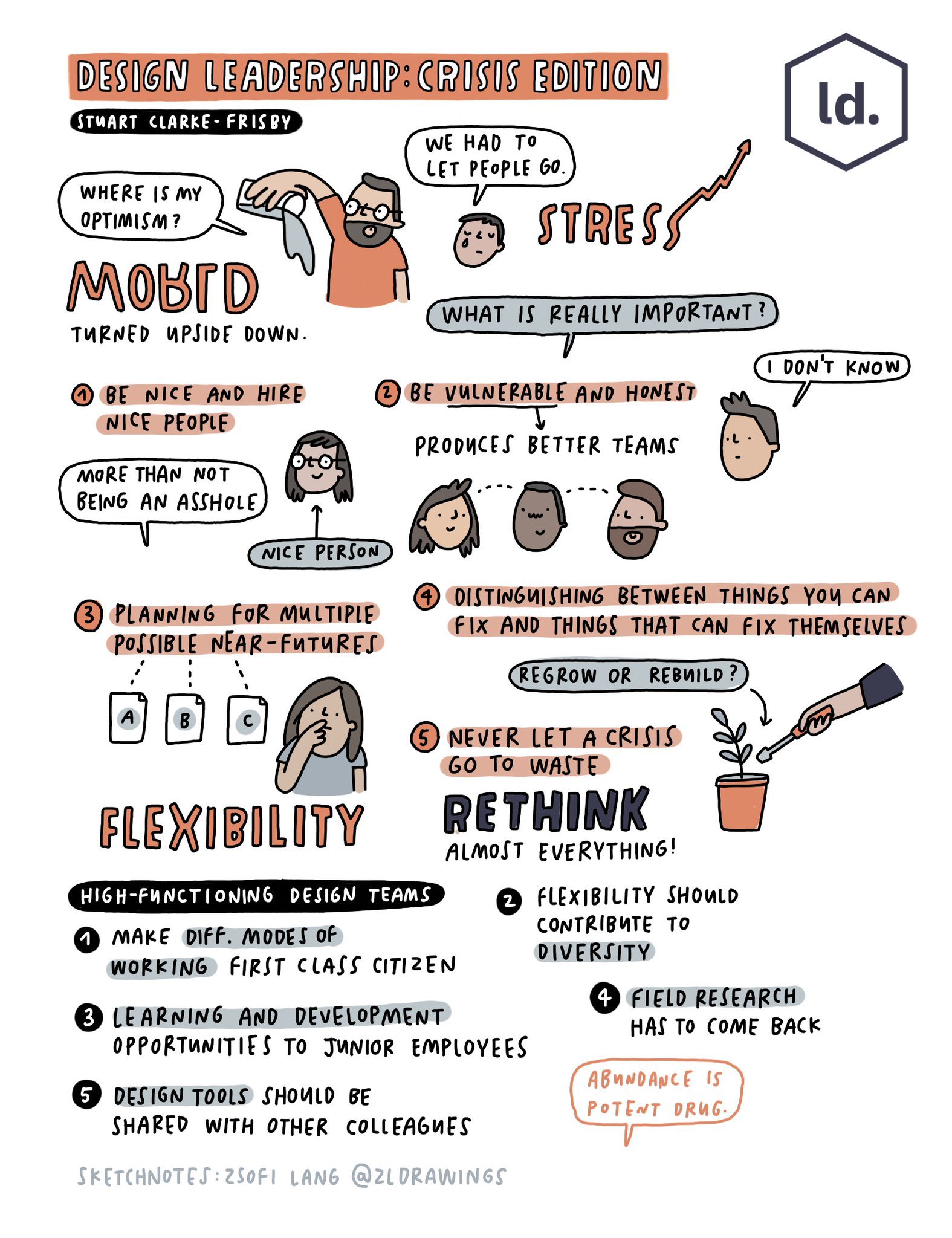

sketch notes by Zsofi Lang

sketch notes by Zsofi Lang

A. an Intro

At this point I feel like I come to Leading Design once per year to regale you all with the latest instalment in my mediocre personal design leadership story, and every year I start out wondering what the hell I could have to tell you all before realising that this in essence 30 minutes of free therapy and I should vent and enjoy myself, so here we are again. I am delighted to have been asked back to present at Leading Design for the fourth time, and as I’ve said on all of those previous occasions, I think this conference represents the best opportunity that current and prospective Design Leaders have to learn, listen and grow, and so it’s wonderful to have been given the opportunity again.

The last time I spoke at Leading Design we were all in the lovely Frobisher Theatre at The Barbican, where I offered some observations on my design leadership career, and how having joined a new company six months prior I was enjoying being able to put in to practise things I’d learnt from other design people at these events, and to correct mistakes I’d made throughout a career littered with them. I talked then about a set of focus areas which I had settled on as my toolset for being successful in my new role and a framework for how I had come to think about design leadership, those areas were:

- Managing through layers of abstraction

- Evangelism & Advocacy

- Scaling beyond my own abilities

- Taking Design from being a service to a strategic asset

- Designing more than just ‘stuff’

- The Design leader as translator

- The Design leader as Contrarian Voice

- Creating good jobs

At the time, these all felt like the appropriate building blocks for doing my job - for creating an environment for good design to happen, and creating an organisation that served a business and the people within it to our collective benefit. I still think these things are sensible areas of focus, and all being well in 2022 perhaps we’ll be able to focus a bit more time and energy on them, but as you’ve probably guessed by this long-winded intro and the telegraphing title of this talk - The days since that last Leading Design and this one have not been like the days that went before them, and my work and the work of all of us has fundamentally changed over the last 12 months into something largely unrecognisable from what we’d come to understand our jobs as. I got into technology as a wide-eyed teenager because it was the palette with which I could draw a wildly optimistic version of the future and then watch it spring to life, and whilst tech has not quite proven itself to be the sunlit uplands where good is rendered upon the world, I have always been able to find at least a seed of optimism in my work, even when things have been difficult before. 2020 was the first year where I felt like the optimism had poured away, not even primarily professionally, but in every aspect of the world. We went from thinking about the best ways to advocate for the early involvement of design in product development processes to trying to work out how best to support a team who are living through an epochal crisis. We went from talking to prospective candidates about the interesting challenges we could offer to them as part of our team, to saying goodbye to our friends and colleagues through redundancies. And so it would be trite to sit before you all today and describe this last 12 months as normal, and instead, I want to try and figure out what we can salvage from the Ashes of 2020-2021, lessons which can tell us something about what we should have been doing differently along, or which we must now absolutely do differently in service of a markedly different world. As much as we’d lament things going back to normal in areas like the use of public space, or the value we place on key workers, we should look inwards and not spurn this hopefully once in a career opportunity to zoom out, reflect and reset for the better. If we don’t do it now, we never will.

B. and Then the Shit Hit the Fan.

I remember the exact moment that I realised things were about to get complicated. I was sitting on a train travelling into central London, in my third week working from the office after relocating from Amsterdam. On this morning, the same train I’d gotten the day before was half as packed, and the usual cold atmosphere of the commute had been replaced with something palpably more worried. A couple of days later our office closed, and like it was for all of you, my world was turned upside down in the space of a few days.

To start with, the novelty and adrenaline carried us along, we managed to muddle through getting stuff done in odd surroundings, but it became clear not long after that the business was facing some significant headwinds as consumer behaviour did a 180 overnight and restaurants started to close. In the course of the early months of lockdown, that struggle would lead to a significant portion of my team being made redundant — including all of the senior leadership of the team bar me, the entire management function, and a significant number of our staff. This was the exact opposite of where I’d talked about being in the last part of my last talk at Leading Design. Instead of being in a position where I was lucky to be helping create good jobs, I was watching good jobs disappear and great people being plunged into chaos overnight. For a team like ours, this was an enormously difficult period — primarily for those of us who left, but also for those left behind — faced with the guilt of having been lucky to have stayed in a job, uncertain of the short-term prospects of the company and the place of our team within it, and all on top of the carnage happening outside - stuck in our homes, isolated from our families, and cruelly unable to even say a proper farewell to our teammates on their last days in the company. Two months into this pandemic, our team was the smallest it had been in years, and the complexities facing our company and our users was greater than it had ever been. Once the dust had settled, I found myself now managing our entire design team and the team itself having been repositioned within the organisation. All of this change in a short period of time clearly made for a stressful environment for everyone, and one in which there were countless questions for which there genuinely was no answer, which whilst understandable, makes for a deeply frustrating context in which to be working.

I don’t want to make this sound uniquely dramatic, I know this same dance was happening in all sorts of places, and whilst it all sounds like a long continuous car crash, in reality it was much more pedestrian, change happened all-at-once, and then very slowly. The reconfiguring of our team and the rebuilding of our culture was going to take time, and along the way we would likely lose more people. I knew then that we faced an uphill battle trying to rediscover what made us all want to be part of this team in the first place.

C. the Stuff You Thought Was Important Actually Wasn’t, You Were Just Lucky You Had Nothing Worse to Worry About.

My list of tools suddenly seemed woefully inappropriate for the task at hand. Like I had turned up brushes in hand ready to paint a fresco only to find that not only had the Cathedral not been built yet, but the land mass it was to be built on was still wet having recently emerged from the ocean. When I had considered that list, I was at the end of an eight year tenure at a stupidly successful company, and I was flush with the naïve optimism that comes from accepting a new job. And had it all been plain sailing I am sure I would’ve gone on thinking that I had most of the tools I needed to do my work, but now I realise that those tools really only applied to that same context in which I’d written them - a company enjoying hockey-stick growth, a design team well established into the fabric of the companies success, and a solid foundation on top of which to build. The tools I needed now were wholly different, and I will now repeat the same mistake here by committing them to video and watching them also become useless a year from now. The tools that got me and my team through 2020 were these:

- Be nice & hire nice people

- Be vulnerable & be honest

- Plan for multiple near-term futures

- Distinguish between things that you can fix, and things that need time to fix themselves

- Never let a crisis go to waste

Be Nice & Hire Nice People

You used to hear lots of talk about Brilliant Arseholes in tech, and then everyone decided we shouldn’t hire them and now our industry is definitely 100% cool.

We need to set a higher bar than not being an arsehole. My predecessors and my peers had the foresight to hire a group of wonderful people who have spent the last year propping each other up and helping each other out, and even when things were a right mess that generosity and kindness never went away. I realised upon seeing the team looking out for each other that this was the kernel of our team culture that needed protecting and encouraging.

As we began hiring again late in 2020, this caring characteristic had become a firm part of our hiring criteria, and a foundational element of what makes for a good addition to our team. It is a core element of what we talk about when we talk about performance, and it is exactly the kind of behaviour which I try and shine a light on and champion.

This isn’t solely because it’s nice to work with nice people - it is good for our collective output, it’s good for our contribution to the business, it’s good for our ability to retain good people. It makes complete business sense to create teams in which people want to work, and that means being nice, and hiring nice people. The risk to the delicate balance of a team culture of hiring someone who doesn’t reflect those characteristics is enormous, and I think I appreciate that now in ways I never did before.

Be Vulnerable & Be Honest

As I mentioned previously, throughout this messy period there were endless well posed questions to which there simply weren’t answers, and I think I realised pretty early on that the right thing to do was to just be honest about that. Earlier in my career I think I’d have tried to save face and give some kind of noncommittal answer, or to go in search of answers where ultimately none would be found.

A pandemic is great cover for being clueless. Very few of us have done this before, and so if there is ever a time to expose ones own limits, this was it. This is a level of vulnerability which would’ve made a younger me deeply uncomfortable, but I have found that once you settle into it, it’s pretty freeing to be able to say “I don’t know”, or “that isn’t something I’ve ever thought about before”. I think this is what I want in a manager, and so perhaps I am projecting here, but I think that being candid is always appreciated, even if the lack of an answer in and of itself is irritating. I once had a manager who was intent on always being right, and was at pains to never not have an answer to a question - I hope his pandemic has been an opportunity to work on that along with the rest of us, because that must be an exhausting way to live.

I have seen my openness and vulnerability reflected back to me in the way my team goes about their work. I think we are more willing to court advise from each other and to throw our hands up and say we need help. We’re more accepting of divergent views or ideas, and we’re more receptive to feedback that challenges our ways of thinking. That all adds up to being a team which can reliably produce really good work, where that work benefits from collective input and generous collaboration.

Plan for Multiple Near-Term Futures

I’ve learnt this past year to be a little less absolutist when it comes to planning — To be more ready to throw a plan away, to plan less rigidly, and to try and plan across multiple possible near futures such that I am better-equipped to deal with change when it inevitably emerges. This manifests itself in a few different areas, but I’d like to focus on just a couple of them for now - How we grow the team, and how we organise around the strategic priorities of the company.

In the first instance, I think I had a bit of a head start here. In a previous role I had become accustomed to staffing budgets oscillating wildly, and so learnt not to place too much focus on them. Over the last twelve months I have gone from planning to grow my team by around 100%, to not hiring anyone for six months, to again looking at ways to sensibly double the size of my team. This leads to a multitude of potential outcomes, several of which justify some kind of planning, which in this case can take the form of a series of scenarios, i.e.

- We meet our hiring targets and double the size of the team by the end of the year.

- Our hiring targets change and we are unable to meet them and adequately support the business.

- We fail to meet our hiring targets and end the year with a short-fall of capacity in a given discipline or business are.

For each of those cases, I have some sort of plan - from a super detailed hiring plan which is used to guide recruiting and ladders up into an organisation-wide hiring plan, to a series of potential mitigation strategies for the non-ideal scenarios. I know where and when I can adjust priorities to meet the most pressing demand, and where I can reshape the existing team to flex in the direction of business priority. Two of those three plans will never be executed, but there is great comfort in the exercise itself, and the certainty that comes from having thought about this series of what-ifs. This isn’t to say that failing to meet our hiring targets will be an acceptable outcome, but at least it will be an outcome that has been considered.

The flip-side of planning for multiple hiring outcomes is to also plan for how best to leverage the capacity already within the team based on that broader context: if we can’t bring in new people, how do we make sure we do the best with the team we have. At the beginning of 2020 our team was made up of a rigid set of silos which made adjusting our allocation to meet the needs of the business was more complicated that it needed to be, and slower than was acceptable either to me, or to our peers in adjacent disciplines. Some of this was a consequence of there being a management staff of n=>1 which naturally increases the amount of time required to discuss and execute on these changes, but some of it was also just the unchecked progress of the team into a structure which would serve it well for predictable growth, but less so for an environment which was changing on a near-daily basis. The team is now much better positioned to respond to the business quickly and without administrative burden.

In addition to the parts of our team domiciled within specific areas of the business, there is also a portion of our staff which are held in reserve to be deployed into the areas with the most complex or urgent needs of the business, and even within the silos, we are working harder than ever before to design across them - to leverage the knowledge we have within the team to work horizontally in an organisational structure which is mostly made up of discrete verticals. This agility has been critical to us doing the work needed over the last twelve months, with a smaller team, there is no doubt in my mind that we’ve been more effective on a per-person basis, and in the aggregate.

The end result of this flexibility in planning and organisational design is a team which is better able to meet the needs of the business, and where the upheaval of working in a new part of the business has been largely eradicated. If tomorrow morning our strategy changed completely, we are in a much better place now to pivot in support of that than we have been at any point before.

Distinguish Between Things That You Can Fix, and Things That Need Time to Fix Themselves.

Changing ones planning approach and moving capacity across the business are the kinds of things which can just be done, once an inefficiency or an externality has been recognised, executing on a change is simple, and ideally the fix is successful. Some things though can’t be rushed, and need time to fix themselves. I talked about that post-redundancy period of 2020 where the team was bruised, and we needed to pick ourselves up off the floor and start rebuilding, but in reality, the rebuilding was more like the regrowth of an organism than the reconstruction of a wall. It would have been deeply insensitive and alienating to have rushed to put that difficult period behind us and start focussing on a bright future, and to a large extent we simply had to let our new reality emerge, and work out how we were going to respond to it. A team culture, a new set of rituals, new ways of working, new ways of communicating - all of these things emerged organically throughout 2020, and by the start of 2021 I felt like we had a team which had carried forth some of the wonderful things which my predecessors had nurtured, and some new things which were a reflection of the things this group had been through, personally, professionally, individually and collectively. There was nothing to be done here other than to wait. To recognise that there were plenty of fixable things to be fixed whilst these intangible cultural assets regrew.

And I don’t think it’s just this kind of thing that is deserving of our patience in times of crisis - It’s worth asking ourselves at the start of any kind of remedial works if we’re trying to rebuild something that needs to regrow, and if so, stepping back and letting it do so organically.

Never Let a Crisis Go to Waste

2020 was a disaster, and I don’t want to suggest otherwise - but I also think it’s important that we don’t let periods of great uncertainty and great change go to waste. They provide rare opportunities for us to rethink everything. In the last twelve months we have seen centuries old ways of doing things turned on their heads, and it would be a failing on all of our parts if we didn’t look at our teams and our businesses and reassess them in this new light.

We started 2020 insisting people spend 1-2 hours per day travelling to a different building so they could talk to each other on slack, we operated on the untested assumption that cross-disciplinary teams worked better when they could gather around the mythical whiteboard, and that a company culture could only flourish over the shared trauma of a perpetually understocked drinks cabinet. That has all changed, and along with it a bunch of things specific to how we design have changed too.

We are designing much more in the open - we have record numbers of non-designers hanging out in Figma, we have Product designers more involved than before in primary research, we have Product Managers & Designers working closer than they ever have. It’s a crying shame that it took something so awful for us to realise these improvements in our ways of working, but let’s not ignore that these things have improved.

When the next crisis inevitably comes along, it will present a similar opportunity to redraw some of the fundamentals, and not doing so would be an enormous waste.

So there are five new things to add to that toolset, perhaps we’ll never use them again, but when the situation demands them, I will be glad to have them in my arsenal.

- Be nice & hire nice people

- Be vulnerable & be honest

- Plan for multiple near-term futures

- Distinguish between things that you can fix, and things that need time to fix themselves

- Never let a crisis go to waste

D. What Does a High Functioning Design Team Look Like in 2022.

I’d like to try and corral this rambling tour of the last 18 months into a leap forward to next year, and to speculate a little bit on what I think the markers of a high functioning Design are in 2022. This is only part prediction, it’s kind of up to us whether this is the future we get or not, and I hope you’ll all join me in working towards making this the version of 2022 we get.

We’ve seen over this last year that we can fundamentally change how we work, for the worse, and for the better. And what is left now as our base is something very different to what we were working with in 2019. So, here’s where I want to see Design teams focussing their thinking for the rest of this year:

- High functioning Design Teams work successfully between location contexts - Remote work is going to be great for lots of people, but swinging violently from an almost completely co-located world to an almost completely remote one will leave some people worse off. When we end up working across the spectrum of remote, flexible and in-office, we have to ensure that these preferences don’t become advantages or disadvantages for our team members. That means making all three of those modes of working first-class citizens. How does a card sorting session work when 25% of the attendees are in the room, and the other 75% are on VC, how does a design sprint remain inclusive and participatory in that same context? This is a great design problem to solve for.

- Flexible working must be a multiplier for progress on building diverse and inclusive teams - It will be a disaster if we do not work out how this new found flexibility in where and how we build our teams doesn’t create opportunities for people who have traditionally been excluded from them. We should be hiring in areas where there are no tech companies, and creating an environment which is welcoming of the people it has historically excluded.

- Distributed teams have to figure out how to nurture junior staff and offer compelling learning opportunities - In my team at least it feels like from March to March we were playing defence, just trying to keep the lights on and do what we needed to to get the pressing work done, and in that process some things suffered, learning and development being primary amongst those. We need to lean in on developing skills in our teams in this new way of working, and specifically need to think about what the early career experience for our team members is, and how we help them build their skills.

- Field Research makes a comeback I worry that the necessary shift towards online user research through UAT tools and virtual panels will have provided such significant financial benefits that we’re going to need to work hard to reclaim some of that research budget for field studies - There truly is no substitute for getting out of the building and talking to people, and that includes international research trips which are key to making sure we aren’t designing for ourselves and people like us.

- Design Tooling becomes tooling for everyone We’ve seen throughout this last 18 months that the tools we use to express our design ideas are being used by lots of other disciplines, and as design teams we need to encourage and facilitate that, if the shared canvas for product development becomes a design tool rather than a word document, we’ll have repositioned design as the shared language of tech and product teams, and then they’ll all be asking for a seat at our table.

E. Closing.

The period we’ve all been living through over the last 18 months has been an unmitigated disaster, and I hope upon hope that we are edging closer towards the end of it. I hope you’re all holding up and hanging in there.

Leadership in crisis is not like leadership in times when everything is going well. In some ways, I am grateful for the opportunity to learn so many important lessons in such a short period of time, and I know that these lessons will stand me in good stead in difficult moments to come. I hope that you’ll reflect on how this time has changed you, and your outlook on leadership, and I hope you’ll consider how you can help build kinder, more vulnerable, more honest design teams, and how you can contribute towards creating a generation of design leaders who are better than we are at all of that stuff. This crisis needs to be a kick up the backside for our industry, and a reminder that when push comes to shove, nothing is unchangeable.

Published on 14 April 2021 – work – presenting – leadership – design – pandemic